This post presents a forgotten BBC Scotland drama series of the 1970s and explains its historical significance and distinctive form. I’ll discuss its treatment of landscape before finally considering how the programme represented tensions between rural and city Scotland.

Although largely forgotten now, Sutherland’s Law (BBC1, 1973-76) was an exceptionally important landmark in Scottish television history. During the early 1970s the BBC operated a special five-year plan for programme development in Scotland, opening new hi-tech studios on the understanding that they would be used to make high-cost productions to a standard suitable for the national audience, which retained a distinctively Scottish identity:

“The low-budget, homespun product justified only by being ‘Scottish’ became unacceptable either inside or outside Broadcasting House. As long as no spurious concessions are made to the wider market of the United Kingdom, it should be a matter of pride that the Scottish product matches the top professional level.” (Annual Report of the National Broadcasting Council for Scotland, 1 April 1973 – 31 March 1974, BBC Handbook 1975, BBC: London, 1974. p.109)

Sutherland’s Law was a high-profile result of this policy. As their first popular drama series made for the national BBC1 audience, a lot of prestige was at stake for BBC Scotland. Exceptional care was taken in setting the programme up, with a pilot episode made (Drama Playhouse: Sutherland’s Law, BBC1, 23 August 1972), resulting in the recasting of Sutherland from Derek Francis to Iain Cuthbertson for the eventual series. This careful preparation helped Sutherland’s Law to become a great success for the BBC, running for five series (46 episodes) and eventually attracting audiences of up to 17 million.

So what sort of programme was Sutherland’s Law? Before I say anything more, I’ll show you the opening credits – the one bit of the programme that people do tend to remember – to see how it presented itself:

This sequence promises two things for the viewer: the prospect of attractive Scottish locations – snow-capped mountains, lapping waves along the coastline, purple heather, wide horizons – and a star vehicle for Iain Cuthbertson. Clever editing positions Sutherland at the centre of this world (despite being on a boat in the first shot and on the shore on the second), as both representative and master of the Highland scene. This romantic impression is accentuated by the choice of theme music, Hamish MacCunn’s nineteenth century romantic overture, ‘Land of the Mountain and Flood’. What the credits don’t do is give you much impression of what this series is going to be about. The only real clue is the word Law in the title.

In fact, the series works as a distinctive hybrid of three types of TV drama: Police, Legal and Community. John Sutherland is a Procurator Fiscal, a position unique to the Scottish legal system. A Procurator Fiscal is something like an American District Attorney, or French Examining Magistrate. In Scottish law the police don’t prosecute, but take their evidence to the Fiscal, who investigates it and then decides whether to lay the case before the Sheriff.

Each episode involves a crime, often a suspicious death, and Sutherland’s investigations can follow a reassuringly familiar detective story pattern. Many episodes also feature the Fiscal prosecuting in court, sometimes extracting unexpected evidence and surprising confessions, working within the highly dramatic established conventions of Courtroom drama.

As we saw in the credits, the figure of Sutherland is intrinsically linked with the landscape, the Argyll coastal resort of Oban, renamed ‘Glendoran’. In addition to the appealing location, the sense of community drama arises through the tensions inherent to the position of Procurator Fiscal, living among the people whom he serves, represents and must sometimes condemn.

The series’ creator, Lindsay Galloway, defined the lot of a Fiscal in terms that emphasised the heroic and empathetic potential of the position:

The series’ creator, Lindsay Galloway, defined the lot of a Fiscal in terms that emphasised the heroic and empathetic potential of the position:

“He must be a man of some dedication. He has to make decisions which will irrevocably change the lives of others; he has to live in a community, yet keep himself a little detached; ideally, he should be a man of deep understanding and compassion.”(Galloway, Lindsay, Sutherland’s Law, Bungay: Pan, 1974. p.6)

“Community drama” is a less readily recognised genre than Police or Courtroom drama, but its function in Sutherland’s Law is best understood as a continuation of Doctor Finlay’s Casebook (1962-1971, BBC Television/BBC1), which had finished a highly successful nine-year run in 1971. Both series present fictional Scottish provincial towns (Tannochbrae and Glendoran) and concern authority figures facing sympathetic dilemmas within these communities. Indeed, both programmes focus upon a similar trio of lead characters; the older man in charge with years of experience to draw upon, the junior Doctor or Procurator Depute from Glasgow or Edinburgh who thinks that his city understanding will fit in the town he moves to, and the housekeeper or secretary who assists through a combination of acute local knowledge and feminine intuition.

Sutherland’s Law featured extensive location filming in Oban and surrounding countryside, presenting a wide variety of distinctive plots revolve around the specific location of Argyll, including; Fishing and seafaring (murders at sea, smuggling illegal immigrants, maritime disasters, riotous visiting sailors)

Sutherland’s Law featured extensive location filming in Oban and surrounding countryside, presenting a wide variety of distinctive plots revolve around the specific location of Argyll, including; Fishing and seafaring (murders at sea, smuggling illegal immigrants, maritime disasters, riotous visiting sailors)

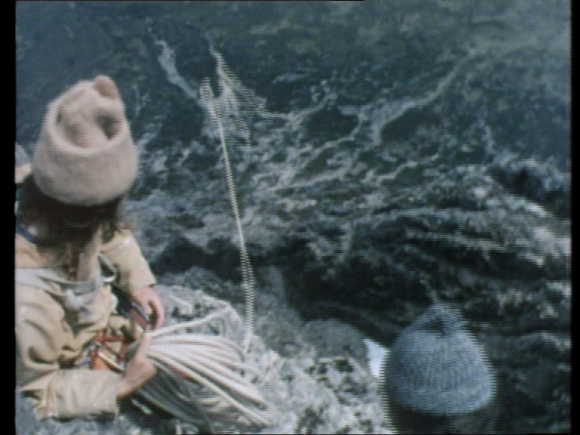

Mountaineering (another murder)

Mountaineering (another murder)

Tragic stories of life on the remote islands (arson),

Tragic stories of life on the remote islands (arson),

– agriculture (pollution that kills a small child) and even winter sports (murder on a sabotaged ski slope).

– agriculture (pollution that kills a small child) and even winter sports (murder on a sabotaged ski slope).

This combination of picturesque setting and crime story leads to a visual trope that reoccurs in several episodes of Sutherland’s Law, in which an attractive pastoral scene –

by the discovery of a corpse, on hillside –

by the discovery of a corpse, on hillside –

Records of contemporary reactions show that expectation of pleasing location settings was central to the appeal of Sutherland’s Law for viewers. The 15 BBC Audience Research reports conducted into the series frequently mention pleasure derived from landscape, especially when this was justified by a relevant storyline:

Records of contemporary reactions show that expectation of pleasing location settings was central to the appeal of Sutherland’s Law for viewers. The 15 BBC Audience Research reports conducted into the series frequently mention pleasure derived from landscape, especially when this was justified by a relevant storyline:

“settings were generally considered exceptionally pleasing, Viewers enjoyed the shots in, around and off Oban for their own sake – especially if they happened to know the West Coast; but it was also felt that the outdoor scenes had been very skilfully used to advance the plot” (BBC WAC, VR/72/497)

Viewers often report approvingly that the Scottish scenery distinguishes Sutherland’s Law from other, urban or American, crime series. When editions are confined to the studio or more prosaic locations, their absence is felt with keen disappointment:

“this particular episode failed to ‘grip’. (…) [It] made less use of outside filming than usual (…) and it was partly the lovely natural settings which made Sutherland’s Law so appealing” (BBC WAC/74/562)

Minutes of the meetings of the BBC Programme Review Board also regularly refer to Sutherland’s Law, and the reactions of the Corporation hierarchy are strikingly different from those of the audience, finding the show over-reliant on attractive settings, which encouraged cosy storytelling: “[The Head of Community Programmes] Rowan Ayers thought the main fault of the series lay in an over-indulgence of the locations” (4 July 1973), offering rather disparaging praise: “[Head of Series, Department of Television] Ronnie Marsh (…) said the series was a wee bit cosy, and its directors did become beguiled by the scenery; but undoubtedly it did appeal to a great many people” (1 September 1976).

Press coverage of the series met these two responses in the middle, expressing pleasure at the setting and pace while also acknowledging a lack of bite:

“plenty of regional colour, and a quiet determination to steer clear of blatant thriller devices. The trouble is that while shunning car chases and plunging-neckline blondes, it has an element of cosiness a long way from the grim realities of early Z Cars and the like. Made in Scotland, the programme shows the region’s usual flair for registering regional character in people and landscape alike.” (Usher, Shaun, ‘It’s not what he says, it’s the way he says it’, Daily Mail, 16 May 1974, p.22)

The final aspect of Sutherland’s Law that I want to discuss with you is how the series represents Scotland beyond Glendoran to its national audience. The cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh often cast negative shadows over Glendoran, threatening Highland values through, respectively, menace and bureaucracy. City visitors are generally unwelcome in Glendoran, one Glaswegian hard man even threatening Sutherland: “I wouldnae like to see a nice old guy like you making a fool of yourself. I don’t doubt for a minute you’re the terror of the local poachers and the guys who throw toffee papers away on the street. Do you not think you’re a wee bit out of your class?” This disruptive force is carried as much by authority figures from the cities as it is by overt criminals: A smooth Edinburgh Insurance Investigator turns out to be in league with visiting bank robbers, and a Glaswegian Detective Sergent engineers the revenge killing of a murderer on the streets of Glendoran, to the disgust of Sutherland, “I prefer the law of the land to the law of the jungle, Sergeant!”

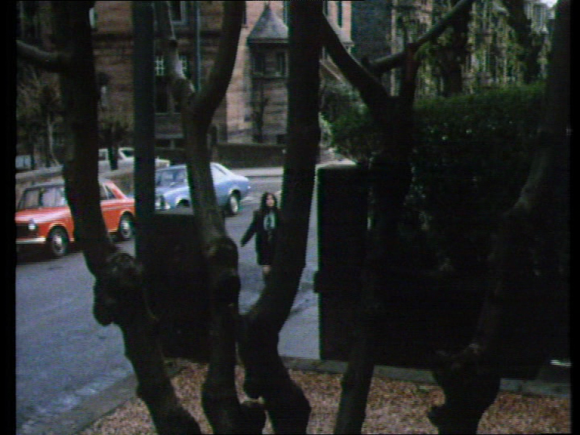

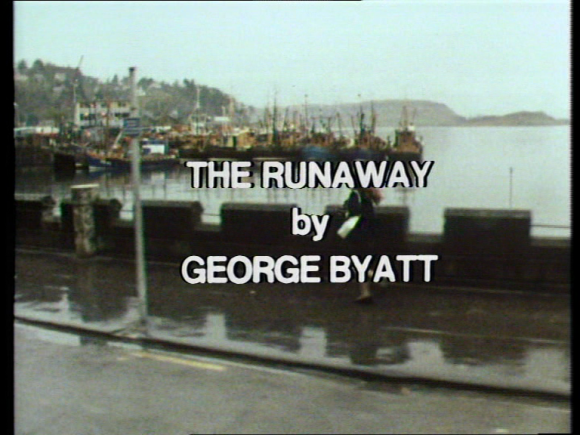

The first series of Sutherland’s Law included location filming in both Glasgow and Edinburgh, contrasting both cities unfavourably with Glendoran. In the episode ‘The Runaway’ (1 August 1973), a schoolgirl absconds to Glasgow. Here are the introductory sequences for each location –

(Clip 1: Glendoran)

The episode works around an essential binary opposition that depicts Glendoran as safe and Glasgow as dangerous. Although the girl is in a distressed state in the first scene, myriad details present her location as a calm, orderly, place – where you can cross the road with confidence and well-behaved children walk the streets – supporting the impression given by the dialogue that Mary (Fiona Kennedy) really ought to turn to Christine (Maev Alexander) for help. Shot selection emphasises the human scale of Glendoran, where even the most imposing features – the church and harbour – can be shown to their full extent while maintaining the recognisable figure of the girl in the frame, emphasising the place of these institutions within the community.

The episode works around an essential binary opposition that depicts Glendoran as safe and Glasgow as dangerous. Although the girl is in a distressed state in the first scene, myriad details present her location as a calm, orderly, place – where you can cross the road with confidence and well-behaved children walk the streets – supporting the impression given by the dialogue that Mary (Fiona Kennedy) really ought to turn to Christine (Maev Alexander) for help. Shot selection emphasises the human scale of Glendoran, where even the most imposing features – the church and harbour – can be shown to their full extent while maintaining the recognisable figure of the girl in the frame, emphasising the place of these institutions within the community.

Glasgow, however, is an alienating place on an outsized scale, where noisy schoolgirls run in packs, and the girl is lost in the crowd – note how the camera now has to seek out Mary. The details that catch the eye in this sequence are of the bizarre (the Hare Krishna) and menacing (the grotesque mask).

This unnerving presentation of Glasgow becomes increasingly magnified throughout the episode. Carefully composed shots use the large scale of the grand streets to shrink characters within details of the architecture –

While Glendoran folk are shown as people who you can turn to, in Glasgow even old ladies are bad people to ask for help –

While Glendoran folk are shown as people who you can turn to, in Glasgow even old ladies are bad people to ask for help –

and from whom you should never accept lifts. –

and from whom you should never accept lifts. –

The effect of the trope of the lone woman dwarfed by the frightening city is magnified by night, when the story reaches its climax –

The effect of the trope of the lone woman dwarfed by the frightening city is magnified by night, when the story reaches its climax –

You don’t want to miss a bus in Glasgow! –

You don’t want to miss a bus in Glasgow! –

– with a near-naked Mary chased into a deserted factory by a pervert (Jon Lauriemore) –

– with a near-naked Mary chased into a deserted factory by a pervert (Jon Lauriemore) –

– a type of terror that never happens in Glendoran in Sutherland’s Law.

– a type of terror that never happens in Glendoran in Sutherland’s Law.

The Edinburgh episode (‘The House’, 22 August 1973) also works around an essential binary opposition, between the humble Highlands and the grandeur of the Capital.

In a story based around the unpromising subject of planning permission, a retired crofter builds a hut on the outskirts of a grouse moor. Because of decisions taken in Sutherland’s absence by his Depute, Duthie (Gareth Thomas), a young man from Edinburgh who works to the letter of the law rather than local knowledge – the crofter’s case is taken to the Court of Session in the capital.

In a story based around the unpromising subject of planning permission, a retired crofter builds a hut on the outskirts of a grouse moor. Because of decisions taken in Sutherland’s absence by his Depute, Duthie (Gareth Thomas), a young man from Edinburgh who works to the letter of the law rather than local knowledge – the crofter’s case is taken to the Court of Session in the capital.

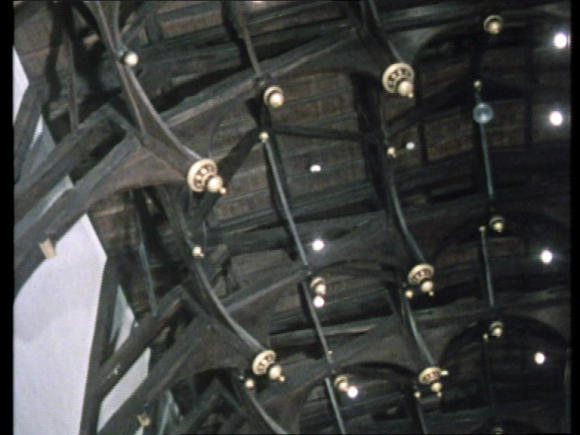

The great hall of the historic Court is presented to the viewer in large-scale heritage mode, the camera eye observing the high-beamed ceiling, many paintings and sculptures, finally settling on the huge stained glass window of James V.

This impressive sight is contrasted by the following scene, which returns to the rubble of the crofter’s demolished hut. The juxtaposition between the two buildings is brutal in its intention, the grandeur of the law as an institution in contrast to the effect of the law upon the individual.

This impressive sight is contrasted by the following scene, which returns to the rubble of the crofter’s demolished hut. The juxtaposition between the two buildings is brutal in its intention, the grandeur of the law as an institution in contrast to the effect of the law upon the individual.

Sutherland is shown as the unique man who can traverse between two landscapes, as both man of the Law and man of Glendoran.

Sutherland is shown as the unique man who can traverse between two landscapes, as both man of the Law and man of Glendoran.

He is the only authority figure shown to be capable of engaging with the crofter, speaking in Gaelic with the old man. There is little doubt where his sympathies lie, though, “It’s a family affair. It ought to be fought on our own doorstep”.

He is the only authority figure shown to be capable of engaging with the crofter, speaking in Gaelic with the old man. There is little doubt where his sympathies lie, though, “It’s a family affair. It ought to be fought on our own doorstep”.

What the credits promise to the viewer, the programme then fulfils – a story that could only be made in Scotland, with a hero whose values are inextricably bound with the landscape he represents. Although Sutherland’s law lay in the upholding of local values, it was a law that greatly appealed to its national audience.

(Text of a paper given by Billy Smart at the University of Glasgow at ‘Screen Studies Conference: Landscape and Environment’ on Saturday 28 June 2014 and at Queen Mary University, Edinburgh at ‘Becoming Scotland: Screen Cultures in a Small Nation’ on Friday 29 August 2014.)

8 replies on “Sutherland’s Law (BBC Scotland 1973-76): Presenting Scottish landscape to a UK audience”

Thanks. Good historical context. What I immediately remembered was Cuthbertson’s commanding presence. Regards Thom.

Excellent post. Interesting to be reminded of a Glasgow of soot-covered buildings (making it easier to portray the city as forbidding?) and Corporation buses. And of Fiona Kennedy when she was young enough to play a schoolgirl. Sadly, Sutherland’s Law seems to have been forgotten to the extent that there’s still no sign of a second DVD set. Here’s hoping.

a superb television series, big iain at his commanding best with beautiful scenery & a wonderful theme tune, sadly forgotten in the annals of tv history hopefully someone will release series 2-4,certainly a missed opportunity for bbc worldwide

[…] Sutherland’s Law, the most successful of BBC Scotland’s early attempts to create a long-running popular drama series, combined elements of the empathetic community drama of This Man Craig and contemporary crime of Daniel Pike. By making the character of John Sutherland a Procurator Fiscal, a position unique to the Scottish legal system (equivalent to an American District Attorney, or French Examining Magistrate) the series could work as a distinctive hybrid of three types of TV drama: Police, Legal and Community. This distinctly Scottish identity was enhanced through the figure of Sutherland being intrinsically linked within a specific landscape, the Argyll coastal resort of Oban, renamed ‘Glendoran’. […]

I haven’t forgotten it – I’m watching it now!

glad to see someone else has posted on this website be wonderful to see the entire series released on dvd

The most remarkable feature of the series was the way it managed to convey real legal issues other than homicides – it is a little depressing to see how critics within the media, even back then, characterised this as “cosy”. Thankfully, then as now, these themes give a great deal more realistic impression of the quite fraught issues that can dominate the lives of lawyers and the police in rural communities, than current police procedurals. A reason, maybe, to revisit this type of setting – indeed the office of procurator fiscal etc perhaps – is the scope to touch on very raw issues in a setting that gives them real drama. After all, over its life, Sutherland’s Law covered a much wider spectrum of Scottish society than River City aspires to do.

[…] Presenting Scottish landscape to a UK audience’, Forgotten Television Drama, available here. […]